When A National Historic Landmark Burns Down, Should We Ask Questions?

More than 70 structures burned in the Grand Canyon National Park, including the Historic Lodge.

After this weekend’s major wildfire run in the Grand Canyon National Park, the public has a lot of questions. After I posted the first images of the Grand Canyon Lodge burning down, I quickly realized this fire would get more public attention than other fires that blew out while using management strategies other than full suppression.

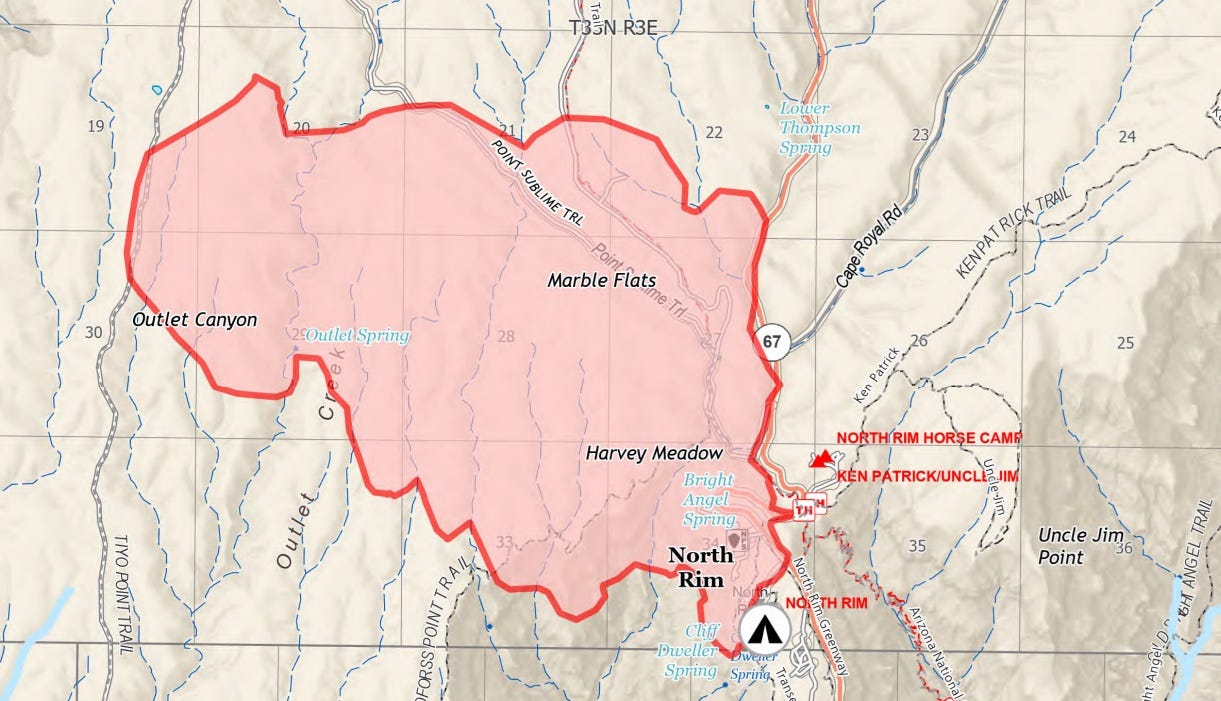

The Dragon Bravo Fire has burned over 70 structures in the Park, and due to the fire, the North Rim of Grand Canyon National Park will remain closed for the duration of the 2025 season. The North Rim of the Park receives about 500,000 visitors a year, significantly less than the South Rim, but it’s still a lot of traffic.

The lightning caused White Sage Fire, which also contributed to the Park’s evacuation, has closed a 87-mile stretch of Highway 89A.

The impact of the Dragon Bravo Fire is enormous. It is very high profile, not just in the traditional media but also across the spectrum of fire managers and firefighters in the United States. The questions being asked by traditional media are also quite different from those being asked by fire managers and wildland firefighters.

But the main questions I’m hearing are “why didn’t they put the fire out?”, and “why did they just let it burn?” Both are really good questions, and come at a time when the conversation around aggressive full suppression tactics on all wildfires heats up. This fire, and its destruction of a historic national landmark, adds fuel to the fire.

It’s really easy to take both sides and play Monday Morning Incident Commander for a fire like this, a lightning-caused fire that had a confine and contain strategy.

Should they have just put it out?

Did the Park have a really good precedent from past successful fires being managed this way?

You can answer yes to both those questions… But let’s first look at the Park’s strategy decisions for the Dragon Bravo Fire leading up to this weekend’s nightmare scenario.

The Dragon Bravo Fire began on July 4, 2025, as a result of a lightning strike within Grand Canyon National Park. The fire was initially managed with a confine and contain strategy, which included multiple containment features to protect structures, facilities and infrastructure. Firefighters had constructed containment lines and were prepared to conduct a defensive firing operation before conditions rapidly changed.

Dragon Bravo Fire Management

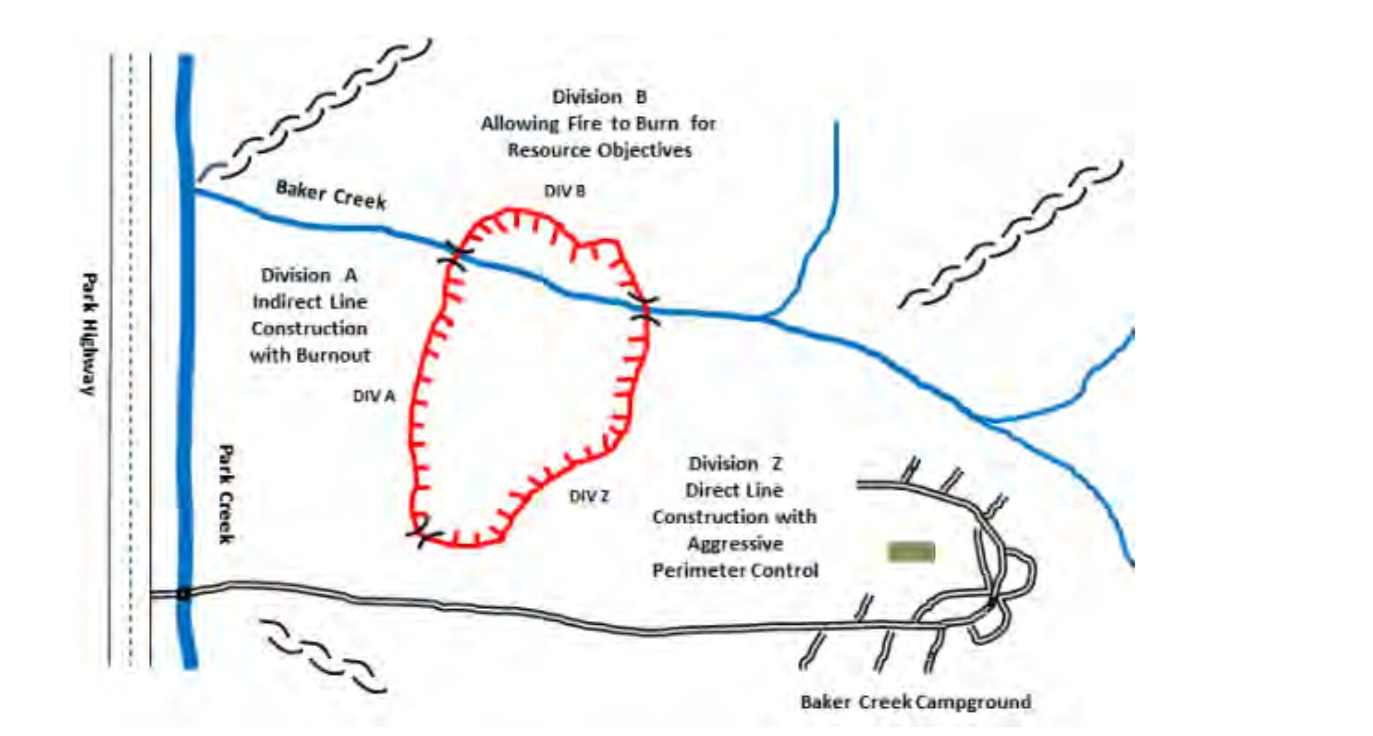

These confine/contain fire strategies are defined as:

“Restricting the spread of a wildfire to a defined area, using a combination of natural and constructed barriers that will stop the spread of the fire under the prevailing and forecasted weather conditions until the fire is out. This includes some actions (for example, line construction or bucket drops) to suppress portions of the fire perimeter.”

This is also different than a full suppression fire:

“A strategy to ‘put the fire out’ as efficiently and effectively as possible, at the minimum possible acreage, while providing for firefighter and public safety. Synonymous with Full Perimeter Containment and Control. (209 User’s Guide, NWCG)

This may help to visualize what the Confine/Contain strategy looks like, which was initially used for the Dragon Bravo Fire. This infographic is from the National Park Service’s Wildland Fire Management Reference Manual:

While some aggressive action may be taken on portions of the fire, other sections may be left to burn.

Now, I don’t think it’s controversial to say these strategies did not work in this case. The fire blew out with the incoming weather and burned down over 70 structures, including a historic landmark that was nearly 100 years old. The North Rim is closed for the rest of the season, and a water treatment plant was burned, causing a toxic chlorine chemical spill.

However, I think it’s fair to say that these strategies were working up until they didn’t. Fire activity on the Dragon Bravo Fire back on July 9th is what I would consider fairly mellow.

But as we know, that all changed this weekend.

To better understand their thinking for how they managed this fire, you have to ask, does the Grand Canyon National Park have a precedent for not fully suppressing a lightning-caused start that was successful?

Well, yes… The Dragon Fire.

The Dragon Fire started in the Grand Canyon National Park on July 17th, 2022. The Park actually had a more hands-off approach to this fire, using a monitor strategy.

The lightning-caused fire is being closely monitored and allowed to fulfill its natural role in a fire-dependent ecosystem.

Wildfire is a natural process within the fire adapted ecosystem on the North Rim. By allowing the Dragon Fire to carry out this natural process, a variety of resource objectives will be met including reduction of hazardous fuels, promoting forest regeneration, improving wildlife habitat, and restoring a more open forest understory.

(Subscriber submitted video of the 2022 Dragon Fire)

Dragon Fire Management: July 2022

A photo taken from the now burned-down North Rim Lodge in 2022 shows the Dragon Fire burning in the Park.

An interesting note about the 2022 Dragon Fire, firefighters found a body on that incident that solved a missing persons case from 2014. I did an entire podcast on it.

So, the Park has a recent history of successfully managing a wildfire using tactics other than full suppression, in the exact same location. We have to at least give them that when discussing how this was managed.

Now, could this have been prevented? The straightforward answer is yes. They could have fully suppressed the Dragon Bravo Fire and thrown the world at it to stop its initial progress early on. However, if they did that, there would be questions about why they didn’t let a natural fire burn, like they successfully did in 2022, to benefit the natural habitat in the Park.

But the reality in this case is the fire got out, created a chemical spill that caused firefighters to back out, which led to the burning of a historic landmark… and the rest is history.

There was a joint memo signed by the Secretaries of the USDA and DOI on wildfire response in May. While the Forest Service does not oversee National Park activities, the Chief of the Forest Service also weighed in on managing fires in May, saying they may have to be limited at a Preparedness Level 3, definitely above that.

I think it’s important to note that the National Preparedness Level increased to a PL4 the morning the Dragon Bravo Fire blew out, and then they transitioned to a full suppression strategy.

“With our current fire conditions, we need to use our firefighting capacity as efficiently as possible. There may be very limited opportunities for in-season prescribed fire or the use of natural ignitions to safely reduce future wildfires outlined in the Interagency Standards for Fire and Fire Aviation Operations.”

Also: “focus on safe, aggressive initial attack,… It is critical that we suppress fires as swiftly as possible to minimize the amount of fireline exposure and be ready for the next ignition. This means employing direct attack tactics when and where feasible to minimize fire size and time to containment when safe and practicable to do so.”

Chief Schultz, Forest Service

Yes, I understand this language is not coming from the DOI, which oversees the National Park Service. However, there have been numerous press conferences and press releases stating that the USDA and DOI align on wildfire strategies.

It’s clear the public is looking for someone to blame for this. But I will ask this question… is the strategy to blame?

I am biased… I like the idea of using natural lightning-caused wildfires for the purpose of letting fire propagate across the landscape in a low-intensity fashion. But the truth is, the last three years have inflicted numerous black eyes when it comes to convincing the public that this is the appropriate thing to do… in some cases, not all. And low intensity seems to become high intensity much faster now.

People ask, “What were they thinking letting this burn?” I mean… look at the Arizona drought map from earlier this month.

But then you look at the June rainfall map, in some places, Arizona received record rainfall. So even though there is some form of drought across 100% of Arizona, maybe the June rains gave a false sense of security.

The public is pissed off that this fire got out and burned down basically all the structures and the Lodge on the North Rim. And quite frankly, rightfully so. Just as they were justified to be angry about the Calf Canyon, Hermits Peak, Cerro Pelado, and other fires deemed to be mismanaged.

If we are to change national policy back to an aggressive initial attack of ALL wildfires, there definitely needs to be a common-sense compromise… Very aggressive prescribed fire implementation in the shoulder seasons, Spring and Fall. And on top of that, pay wildland firefighters hazard pay during these operations, which they currently do not receive for Rx burns.

Could they have put the Dragon Bravo Fire out to prevent this from happening? Yes. However, you could argue this contradicts the Parks wildfire management plan, which they successfully implemented in July 2022 with the Dragon Fire.

So I ask this final question… It’s not who’s to blame; the question is, does the national wildfire response strategy need to shift to a more aggressive initial attack response across the board? National Parks, Forests, and other lands?

Is that the route to go IF we drastically increase prescribed fire and fuels management projects? Is it fine the way it is, and we just have to convince the public that this happens once in a while?

Because if we don’t do the latter, it might be hard to get buy-in. If we keep burning down National Landmarks with fires that do not have a full suppression strategy, the public may force that policy for the wildfire community on their own.

I’d love to hear your thoughts.

THE HOTSHOT WAKE UP — Thank you to all of our paid subscribers. Your support allows us to donate generously to firefighter charities and supports all of our content. You also receive all of our article archives, more podcast episodes, Monday morning workouts, and also entered into our giveaways, plus more.

I’ve worked on the Kaibab Plateau on various forestry projects since 2002. The nature of that landform (generally uninhabited and almost entirely federal land) is that it allows managers to let fires burn for resource benefit pretty often, and at large scales. The cooperative relationship between GCNP and KNF Fire programs facilitates cross boundary RX as well as wildland fire use. Occasionally there are big blowouts such as Warm, Mangum, and now White Sage. GCNP and Kaibab NF know their shit when it comes to fire. Tons of experience. The question I am asking is why the hell wasn’t the lodge and other facilities already prepped adequately? Especially since they sent all the tourists off last Thursday and had plenty of time for project work around the site. This really surprises me and gets my conspiracy theorist mind cranking.

I think maybe there should be a programmatic review after this season.. similar to the prescribed fire review. There may be commonalities that we can't see when we look at a fire at a time. Also it seems like there are way different approaches among agencies and units within agencies.. do all work equally? What do communities think about different ways of interacting with them? This kind of in-depth review could take awhile but would be ready by next summer.